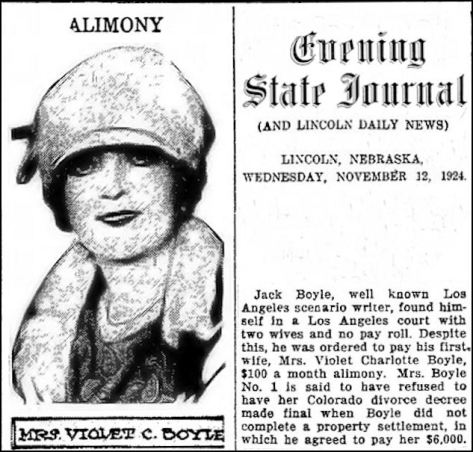

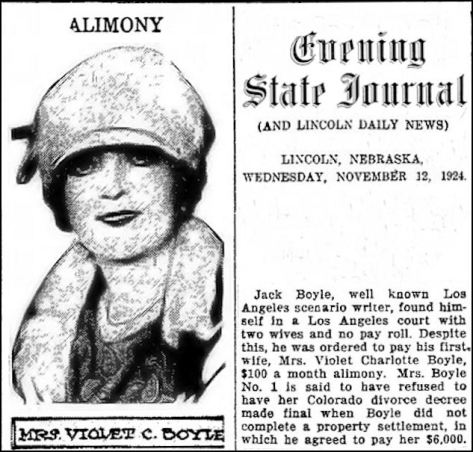

So much of Jack Boyle’s life is shrouded in obscurity, half-truth and exaggeration, it is hardly surprising that details about his first marriage are difficult to pin down. His wife’s name was Violet — or Charlotte — or Trixie — or perhaps something else altogether. Just when and where the couple tied the knot is equally questionable. Here is what can be gleaned from contemporary newspaper accounts and other records of the time:

Shortly after his release from Canon City Penitentiary in late 1914, Boyle took up with a woman calling herself Violet Wilson. She was reputed to have been a reporter for an unspecified Denver, Colorado newspaper, and to also have gone by the name Trixie Dean. When Boyle left Denver in February 1915, Violet went with him, and at the time of the pair’s arrest in Kansas City, Missouri a few weeks later, newspaper accounts described her as Jack’s wife. The man who paroled Boyle, Warden Thomas Tynan, expressed surprise in hearing of his former inmate’s marriage, saying that no mention of this had been made to him when Boyle requested permission to move out of state to accept a reporting job. But from their 1915 arrival in Kansas City to their abrupt departure in 1917, Jack and Violet lived there as husband and wife.

The same can be said when the couple resettled in Baraboo, Wisconsin, and Jack’s 1918 draft registration card listed Violet Boyle as his nearest relative. This tallies with Variety‘s October 8, 1924 article which later reported that Boyle and Violet had been married in Crown Point, Indiana on March 25, 1918. While this would mean that previous references to to the couple as man and wife were erroneous (perhaps referring to a common law marriage, rather than a civil ceremony) the Variety article would at least seem to put the mystery of the Boyles’ wedding date to rest. Except that the marriage records held in Crown Point indicate that the couple were wed in 1919. So there is no simple answer to the question of when Jack was first married.

Regardless, the union did not last long. By mid 1921, reports began appearing in various newspapers that the couple were separated, and that Violet had filed for divorce in the State of Colorado. However, many of these reports now called the soon-to-be-ex Mrs. Boyle by the name Charlotte (Violet’s middle name). Still later items circa 1923 stated that Violet went to Hollywood in hopes of becoming an actress, citing drama training she received during her youth in Norway. She even hoped to land roles in the movie adaptations of some her ex-husband’s stories.

Today, a review of various genealogy websites reveals that Violet began life as Hanna Charlotte Petersen. Born in Trondheim, Norway in 1883, she immigrated to the U.S. in 1903. How she came to take the names Trixie Dean or Violet Wilson is unclear, but she is known to have returned to Colorado after her mid 1920s stint in Hollywood. She remained there at least through 1954, but is reported to have died in Los Angeles on April 1, 1971. She outlived Jack by more than 40 years and, in light of their rather tumultuous split, appears to have had a final laugh at his expense. In June of 1932, literary agent Larry Giffin of New York published notices seeking the administrator of Jack Boyle’s estate, to obtain permission to print one of the author’s stories. A few days later, an item appeared in The Portland Oregonian stating that Giffin’s search had ended, having located Boyle’s widow in Denver. Since Jack’s wife at the time of his death, Elsie, never lived in Colorado, it sounds as though Violet was still finding ways to derive a bit of income from her ex-husband’s work, even four years after his death.

JBF 5/25/15

http://boards.ancestry.com/surnames.dinkel/97/mb.ashx

http://www.geni.com/people/Hanna-Boyle/6000000012472762226

Permalink

Leave a Comment

In April 1920, at the height of his creative output on Boston Blackie, Jack Boyle was put in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison in New York, and managed to walk away to tell the tale. The incident didn’t make headlines, but was picked up by a handful of newspapers, including Wisconsin’s Baraboo Daily News (April 23, 1920) and The Portland Oregonian (August 1, 1920). .

This was hardly the first time Boyle had seen the inside of a penitentiary, but when he stepped within the walls of Sing Sing in 1920 it was amidst a rare circumstance for the convict turned author. He had not been sentenced to serve time there. Instead, he was in the facility at the invitation of Warden Lewis E. Lawes, to gather background material for an upcoming prison movie he was reported to be writing for director Frank Borzage. In fact, director Borzage and Viennese scenic designer Joseph Urban accompanied Boyle on his tour of the penitentiary, which afforded them each the morbid thrill of sitting for a few moments in Sing Sing’s infamous death chair. Given Boyle’s criminal past, and having published stories of convicts condemned to execution, sitting in the electric chair must have been a perverse experience for him.

Whether or not Boyle ever wrote the screenplay for his proposed prison story is unknown, but no such production was ever directed by Frank Borzage (whose career helming feature films stretched from 1916 to 1961). However, Borzage did collaborate with Joseph Urban on two films in the years directly following their visit to Sing Sing — GET RICH QUICK WALLINGFORD (1921) and BACK PAY (1922). Coincidentally, the WALLINGFORD film was based on the work of another popular author of crime fiction, George Randolph Chester, and featured a confidence man known as Blackie Daw.

Joseph Urban eventually had a much more direct connection to Boston Blackie, working as the set designer on the Jack Boyle sourced feature films BOOMERANG BILL (1922) and THROUGH THE DARK (1924). But its possible that Urban was a part of something even more significant in Boyle’s personal life. Apart from his movie work, throughout the early 1920s Urban was heavily involved with set design for the Ziegfeld Follies. It was during his 1920 visit to New York that Jack Boyle met Elsie Thomas, the woman soon to become his second wife. At the time, Elsie was a dancer in the Ziegfeld Follies. So, along with sitting in the electric chair with Boyle that night in Sing Sing Prison, Urban may have been party to Jack’s introduction to the next Mrs. Boyle.

JBF 5/18/15

Permalink

Leave a Comment

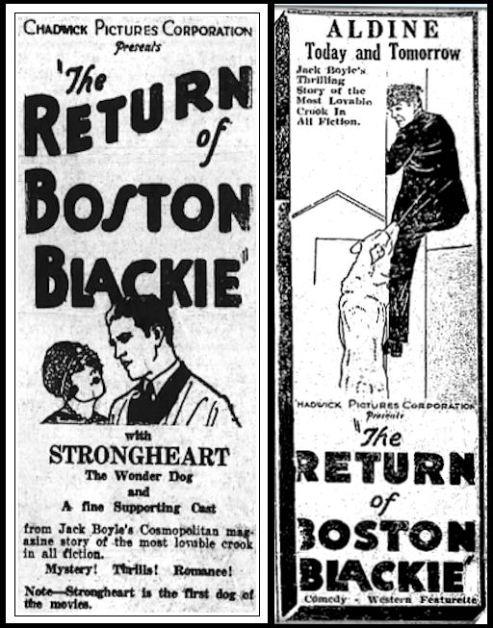

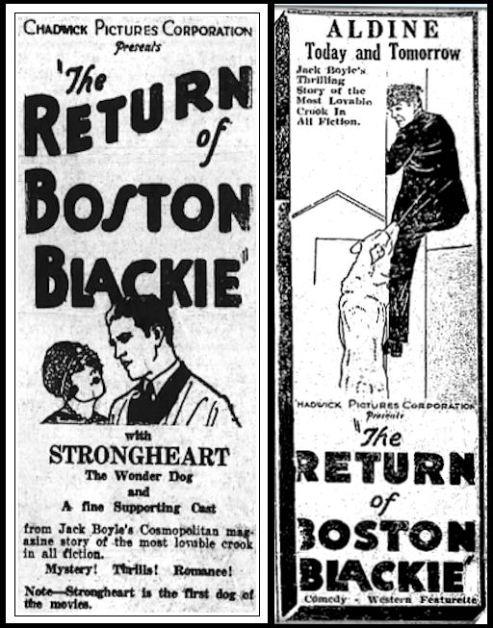

This week’s treat from the archives is a pair of rarely-seen newspaper ads promoting the last of the silent Boston Blackie films — Chadwick Pictures’ August 1927 release THE RETURN OF BOSTON BLACKIE:

The film featured Bob Custer (billed under the stage name Raymond Glenn) in the role of Boston Blackie. Despite the ad’s claim that the film is “from Jack Boyle’s Cosmopolitan magazine story,” no such tale of Blackie becoming involved with a young girl and a stolen necklace appears anywhere in Boyle’s output. However, the presence of a prominent canine character suggests some loose inspiration may have been drawn from his Blackie story “Black Dan” which appeared in the October 1919 issue of THE COSMOPOLITAN.

JBF 5/11/15

Permalink

Leave a Comment

When The American Magazine published the quartet of tales which introduced Boston Blackie to the world in 1914, readers were treated not only to the watershed stories of Jack Boyle’s literary career, but also to the graphic artistry of a master illustrator. These early Blackie yarns were graced by illustrations from rising American artist N.C. Wyeth. Each story was accompanied by several original Wyeth compositions, all rendered in beautiful black and white. Several excellent artists illustrated Blackie’s magazine adventures over the years – W.H.D. Koerner and Lee Conrey, to name just a pair – but Wyeth’s work on the series is in a class by itself.

Which makes it all the more exciting to discover a couple of Boston Blackie images that have never been published the way Wyeth originally rendered them. While The American presented these pieces gorgeously in black and white, the artist painted at least some of them in full color. So, while Wyeth’s work on Boston Blackie has been available to the public for literally as long as the character has existed, almost no one has seen the paintings the way they actually appeared resting on the artist’s easel.

Happily, the Brandywine River Museum in Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania is home to many of the original canvases of N.C. Wyeth, and among them are at least two full color images from Jack Boyle’s very first set of Boston Blackie tales. These images cannot be reproduced here (as they are copyrighted to the Brandywine Museum), but for your enjoyment I will present links to them as they appear on the museum’s website:

http://brandywine.doetech.net/Voyager/image.cfm?ImageKey=9785&ImageFile=/VoyagerImages/BRM_93.23.jpg&TableKey=OBJECT:1213155

This first painting was highlighted in the October 1914 story “A Thief’s Daughter,” and features an image of Mary, before her marriage to Blackie, preparing opium for a group of her father’s friends. Blackie is among the group.

http://brandywine.doetech.net/Voyager/image.cfm?ImageKey=9493&ImageFile=/VoyagerImages/BRM_96.1.13.jpg&TableKey=OBJECT:1278033

And this image comes from the September 1914 tale “Death Cell Visions,” in which Blackie and his cellmate are visited nightly by a ghostly apparition.

While Wyeth’s Blackie illustrations are among the finest done for the series, apparently N.C. Wyeth himself was less than thrilled to be doing such commercial work. The Brandywine’s notes on the “Death Cell Visions” piece include the following comments:

In May, 1914 Wyeth wrote, “To-day on my easel stands a canvas vividly portraying two murderers in a death-cell. The apparition of a hideous blood stained face stares at them from the wall. It is only by using my utmost power of control that I do not get up from this note and destroy the damned thing! But patience! I see the opening clear, where I can choose what kind of thing shall be my output.”

Regardless of Wyeth’s feelings regarding his commercial work, his illustrations for Boston Blackie’s debut run in The American are fantastic visualizations of Jack Boyle’s scenes, and are well worth the effort of any Blackie fan to view them. Many more are available on the Brandywine’s website, accessible simply by running the name Blackie though their catalogue’s keyword search. I highly encourage everyone to take the time to give it a look.

JBF 5/4/15

Permalink

2 Comments